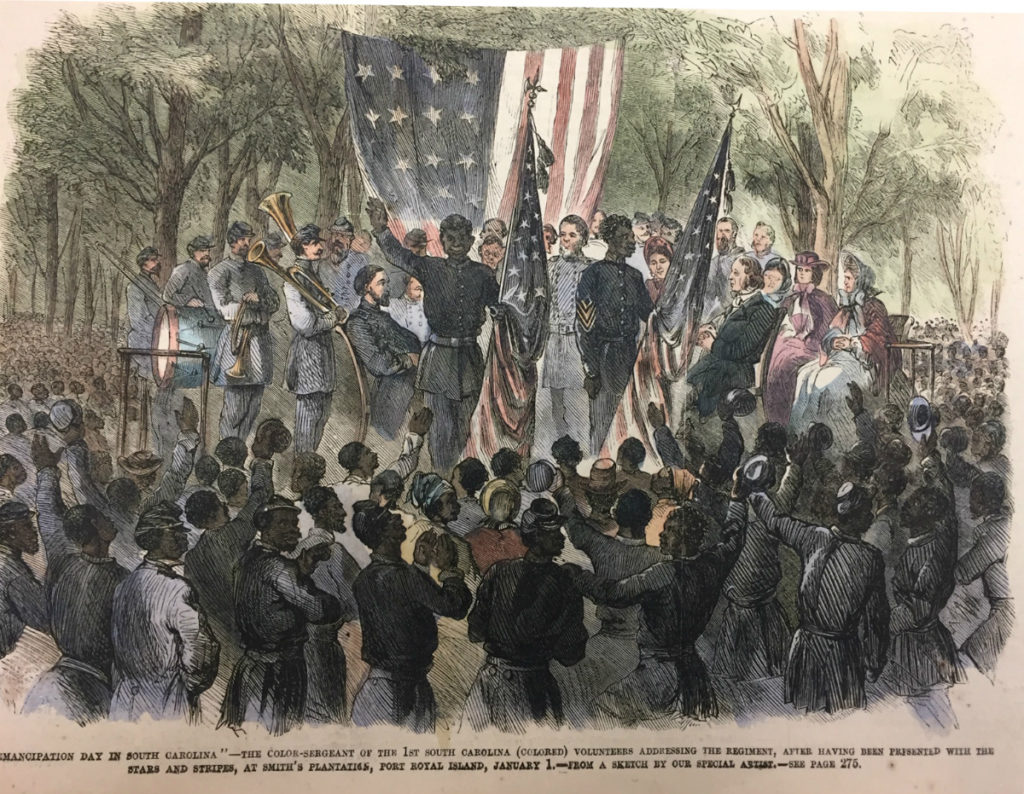

Pictured above is a hand-colored 1863 image (Frank Leslie’s illustrated newspaper) of the Emancipation Day celebration on Jan. 1, 1863, under a grove of oaks outside Camp Saxton along the Beaufort River. Columbia filmmaker and Charleston native Bud Ferillo, who provided the engraved image, tells us that celebration of the first Emancipation Day was the largest in the South of freedmen when sine 3,000 people attended. Today, the location is home to Naval Hospital Beaufort.

By Herb Frazier | Today at noon, the Charleston community will gather at Morris Brown AME Church to celebrate a moment in history when enslaved people anticipated freedom.

This special event at Morris Brown will be an homage to services first held on Dec. 31, 1862. At that time, the enslaved met in praise houses and churches to await the end of slavery with the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863.

Those first freedom’s eve services in 1862 have become an annual celebration called Watch Night held on New Year’s Eve in black churches across America. While many congregations, like Morris Brown, have held this service its original purpose had been lost in time. Last year, the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission began an effort to preserve and sustain this cherished tradition.

The service at Morris Brown will be Charleston’s first-ever community-wide Watch Night event. Instead of beginning a few hours before midnight, this two-hour service will start at noon. It will feature poetry reading, traditional songs and food, drummers and dancers. It will be time for reconciliation and thanks for the past year and resolutions for the year to come.

This event is co-sponsored by the Morris Brown, the 7th Episcopal District of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Magnolia Plantation and Gardens, and the commission. The commission, established by Congress, encourages the preservation and promotion of the Gullah Geechee culture in the coastal regions of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and northern Florida.

“Watch Night, traditionally, has both spiritual and cultural significance in our community. Spiritually, a new year brings another God-given opportunity to reach our full potential,” said the Rev. James A. Keeton Jr., Morris Brown’s senior pastor. “Culturally, as descendants of people who were enslaved and objectified by laws and practices, a new year is not only a testimony of survival, but it also gives hope that the new year will be better than the current one.”

Watch Night services are an opportunity to educate people about an important chapter in American history, said Heather Hodges, executive director of the commission, headquartered on Johns Island. “Many people are unaware that the Emancipation Proclamation only applied to a handful of states that were considered to be in open rebellion, like South Carolina, and it did not emancipate all of the enslaved in the country.

“This means that in 1863 the ancestors of the Gullah Geechee people were among the first to begin to emerge from bondage,” she said. “Their experiences before and during this period of the conflict, then subsequently during Reconstruction, formed an important part of South Carolina history that many know little about. We cannot underestimate the significance of what the promise of the Emancipation Proclamation meant to the enslaved, and we must always gather on Watch Night to commemorate their sacrifices – and to celebrate their freedom.”

The service at Morris Brown on Morris Street in downtown Charleston is one of about 46 confirmed Watch Night services planned in the Gullah Geechee Corridor.

A watch night service is not unique to African American congregations, said Dr. J. Herman Blake, a founding member of the Gullah Geechee commission and professor emeritus at the Medical University of South Carolina. Other faiths and cultures have held watch night services as a way to celebrate the new year.

But the watch night service took on a new meaning on Dec. 31, 1862, as people of African descent in the Beaufort and Port Royal areas awaited the Emancipation Proclamation signed by President Abraham Lincoln. During the Civil War, the Union invaded Port Royal and occupied Port Royal and Beaufort in November 1861. The area remained under Union control throughout the war, allowing for the enslaved communities there to become officially free on Jan. 1, 1863.

As they waited for freedom, enslaved people gathered under a large oak tree at Camp Saxton and the following day they heard a reading of the Emancipation Proclamation. That tree still stands today on the site of the U.S. Naval Hospital in Beaufort.

- Have a comment? Send to: editor@charlestoncurrents.com

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!