Charleston Currents #12.10 | Jan. 13, 2020

LAUGHS AND GAFFES: The premier comedy event in the South, the Charleston Comedy Festival, starts its four-day run Jan. 15 with more than two dozen shows across town. Learn more about the event, brought to you by the Charleston City Paper and Theatre 99, in today’s calendar below. Above: Comedians doing improv at a past festival. Photo via Charleston City Paper.

TODAY’S FOCUS: Charleston, North Charleston to honor King over next week

TODAY’S FOCUS: Charleston, North Charleston to honor King over next week

COMMENTARY, Brack: Finish the job to make 4-year-old kindergarten statewide

IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Charleston Gaillard Center

NEWS BRIEFS: General Assembly to reconvene Tuesday

FEEDBACK: Send us a letter

MYSTERY PHOTO: Pointy top

S.C. ENCYCLOPEDIA: A history of our General Assembly

CALENDAR: Charleston Comedy Festival set for Jan. 15-18

Charleston, North Charleston to honor King over next week

Staff reports | Charleston-area residents will have multiple opportunities over the next week to honor the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as the region remembers his sacrifices and leadership in the days leading up to next week’s federal holiday.

The YMCA of Greater Charleston is coordinating most of the events, including these highlights:

- MLK Racial Equity Institute, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., Jan. 16-17 (sold out).

- MLK Youth Poetry Slam, 2 p.m to 4 p.m., Jan. 18, Charleston County Public Library, Calhoun St., Charleston (register).

- MLK Ecumenical Service, 4 p.m. Jan. 19, Mount Moriah Missionary Baptist Church, North Charleston. More than 1,000 people are expected to attend the event, which will feature a keynote address by Bishop Vashti Murphy McKenzie, presiding prelate of the Tenth Episcopal District of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church.

- MLK Parade, 10:30 a.m., Jan. 20, downtown Charleston (details).

- MLK Commemorative Concert, 5 p.m. Jan. 20, First Baptist Church of James Island (details).

- MLK Breakfast, 7:30 a.m., Jan 21, Charleston Gaillard Center (tickets). The keynote speaker will be entrepreneur and philanthropist Sheila C. Johnson, founder and CEO of Salamander Hotels & Resorts, co-founder of the Black Entertainment Television (BET) network, producer of the critically acclaimed film “The Butler,” and the first African American woman to achieve a billion-dollar net worth. Charleston Mayor John Tecklenburg will serve as the event’s honorary chair. More than 700 leaders are expected.

- MLK Youth Summit, 9 a.m., Jan. 21, Charleston Gaillard Center.

- MORE INFO. Learn more about the 2020 MLK Celebration online at ywcagc.org/mlk.

There’s also a free King tribute concert at 5 p.m., Jan. 18, at St. Matthew Baptist Church, 2005 Reynolds Avenue, North Charleston. The City of North Charleston Cultural Arts Department will sponsor an annual Martin Luther King Jr. tribute concert by the renowned group Lowcountry Voices. Admission is free, but an entry ticket is required. To learn about tickets or the concert, call 843-740-5854.

Finish the job to make 4-year-old kindergarten statewide

By Andy Brack, editor and publisher | The math is easy. With about about $2 billion in new or surplus tax revenues for the state’s coming fiscal year, there’s more than enough money for the General Assembly to do something it should have long done: Make 4-year-old kindergarten available for all of South Carolina’s poor children.

Traditionally, kindergarten begins in public schools for 5 year olds. But starting earlier in school makes a difference, according to study after study. For South Carolina to get more at-risk kids in kindergarten, the state will have to steer about $50 million to 4K programs out of the $1 billion in the state’s new recurring revenues — money that will come to the state without raising taxes because of old-fashioned growth.

Traditionally, kindergarten begins in public schools for 5 year olds. But starting earlier in school makes a difference, according to study after study. For South Carolina to get more at-risk kids in kindergarten, the state will have to steer about $50 million to 4K programs out of the $1 billion in the state’s new recurring revenues — money that will come to the state without raising taxes because of old-fashioned growth.

This is a no-brainer. And, it seems, it’s now something Republican and Democratic leaders actually agree on. Gov. Henry McMaster, a Republican, also reportedly will call for more 4K money when he releases his budget recommendations as the General Assembly reconvenes next week.

“We may take it the rest of the way,” said state Sen. Vincent Sheheen, a Kershaw Democrat who for years has been steering more money to help poor 4-year-olds get kindergarten.

GOP state Sen. Greg Hembree, who chairs the Senate Education Committee, said he was for expanding 4K. “We’re not going to make quantum leaps (in education) in the eighth grade, but we can make great strides in the earlier grades,” he said during a legislative preview for reporters.

The time for finishing the job is now. It’s something lawmakers have known for awhile they should do.

Fifteen years ago as the General Assembly was being sued by poor school districts for doling out public education dollars inequitably, it put together a pilot program to offer 4-year-old kindergarten in those districts. The program had success.

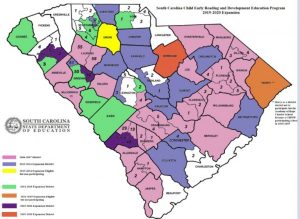

In 2013, Sheheen and other lawmakers worked to expand 4K offerings beyond the 33 districts that were part of the pilot program. By 2016, about 30 more districts received 4K monies for at-risk students based on the district’s poverty rating. If a district had a poverty index of 75 or higher, it got money.

But that left out poor students who lived in more affluent districts where the poverty index could be far below the 75 rating. Those students, just as poor as kids on the so-called Corridor of Shame school districts, couldn’t get access to 4K monies because of their zip code. It was another inequity. At the time, an estimated 8,250 4-year-olds in South Carolina — one in seven of kids this age — were at risk but couldn’t qualify for earlier childhood education.

But that left out poor students who lived in more affluent districts where the poverty index could be far below the 75 rating. Those students, just as poor as kids on the so-called Corridor of Shame school districts, couldn’t get access to 4K monies because of their zip code. It was another inequity. At the time, an estimated 8,250 4-year-olds in South Carolina — one in seven of kids this age — were at risk but couldn’t qualify for earlier childhood education.

Currently in 62 of 79 South Carolina school districts, the state offers free 4-year-old kindergarten to at-risk children, who are defined as those who are eligible to receive Medicaid.

According to legislative sources, this translates to 4K instruction being given to about 13,000 students in the 62 school districts. Another 5,000 qualify to attend free 4K classes, but don’t participate in public programs for one reason or another.

In the remaining 17 districts, about 15,000 students still are not being served by 4K programs. That would be solved if the state ponied up $50 million in recurring revenue.

Thirty-nine poor school districts filed a lawsuit in 1993 saying they were not receiving fair funding. It took 21 years for the case to wind its way through the courts and years for the legislature to do more to reduce inequities in education funding.

There was resistance to the pilot program. The move to expand the pilot program only got funded through a procedural budget move because it wouldn’t have passed on a straight up-or-down vote.

But like a soup that stews for a long time to become more palatable, state leaders finally seem to have understood, matured and accepted that 4K education makes a difference — and to continue to keep it from poor kids who live in more affluent districts also isn’t fair.

In this surplus and election year, let’s hope state legislators have the backbone to complete a job that should have been finished long, long ago.

- Andy Brack is the editor and publisher of Charleston Currents and Statehouse Report. Have a comment? Send to: editor@charlestoncurrents.com

Charleston Gaillard Center

Charleston Gaillard Center provides the Lowcountry with a world-class performance hall, elegant venue space and vibrant educational opportunities that inspire dynamic community throughout the area through the power of the performing arts. The Center’s vision is to enrich the diverse community of Charleston with artistic and cultural experiences that are accessible and unique, and to serve as an educational resource for generations to come.

Charleston Gaillard Center provides the Lowcountry with a world-class performance hall, elegant venue space and vibrant educational opportunities that inspire dynamic community throughout the area through the power of the performing arts. The Center’s vision is to enrich the diverse community of Charleston with artistic and cultural experiences that are accessible and unique, and to serve as an educational resource for generations to come.

Did you know that the Charleston Gaillard Center is a 501c3 non-profit that works with over 25,000 students each year from the tri-county area? Promoting education is one of the core values of the Charleston Gaillard Center and an integral part of our mission. By broadening the reach of arts-education in the Lowcountry the Gaillard Center encourages learning through the arts and serves as a powerful tool for student achievement and personal development while providing people of all ages with the opportunity to cultivate and grow their talents and appreciation for the arts. To learn more about our education initiative, click here: www.gaillardcenter.org/outreach.

For more information, click the links below:

- Buy tickets and see our great events

- Become a member today

- Plan your event at the Charleston Gaillard Center

- Learn about our education and community programs

- Contact the Gaillard Center.

General Assembly to reconvene Tuesday

Staff reports | State lawmakers are expected to buckle down to work when the General Assembly reconvenes for its 2020 session Tuesday. The House likely will start on a bill related to Daylight Savings Time, while the state Senate could head straight into debate on the House-passed large education package.

Also under consideration in the House will be bill that seeks to prohibit approval of an action supporting seismic testing for oil or natural gas on land or in water of the state of South Carolina, as well as a rival bill that would ban state agencies or local governments from impeding plans to deter or prohibit seismic testing infrastructure. See the House calendar here.

Senate Education Chair Greg Hembree of Horry County has said a large education bill that does everything from teacher pay raises to allowing the state to remove chronically failing school boards will be “the first major debate” of the session. Also on the Senate’s calendar are measures to boost higher education funding and to require county clearks to report restraining orders to state law enforcement officials to keep people from possessing firearms. See the Senate calendar here.

In recent news briefs:

![]() Big year. The S.C. Ports Authority said it had its best calendar year in history in 2010, handling 2.44 million twenty-foot equivalent container units (TEUs). That’s a 5 percent annual increase over the previous year, according to a press release. “We enter 2020 with a great decade of growth behind us, during which we doubled our volumes, tripled our asset base and added more than 200 people to our team,” Ports President and CEO Jim Newsome said. “Our cargo growth and efficient terminals are only made possible through the dedication of our team and the broader maritime community.”

Big year. The S.C. Ports Authority said it had its best calendar year in history in 2010, handling 2.44 million twenty-foot equivalent container units (TEUs). That’s a 5 percent annual increase over the previous year, according to a press release. “We enter 2020 with a great decade of growth behind us, during which we doubled our volumes, tripled our asset base and added more than 200 people to our team,” Ports President and CEO Jim Newsome said. “Our cargo growth and efficient terminals are only made possible through the dedication of our team and the broader maritime community.”

Santee Cooper. Statehouse Report correspondent Lindsay Street outlines the stakes of the coming legislative debate over Santee Cooper, the state’s public utility, later this month in the General Assembly. Lawmakers are prepping to determine whether to sell it, change the management structure or simply reform the utility following the $9 billion debacle over a joint project to build new nuclear facilities. Read her story here.

2019-2020 could have $507 million surplus. In a meeting with journalists Thursday, state Revenue and Fiscal Affairs Office staff members offered data showing the current fiscal year is on track to have a $507 million surplus from lowball revenue projections. Add to that another $350 million in surplus funds from the 2018-19 budget. That leaves state legislators with a pot of more than $850 million in surplus funds to be used for non-recurring expenses. Executive Director Frank Rainwater told Statehouse Report said the agency missed the revenue forecast largely due to “volatile” revenue sources difficult to predict, such as corporate income tax, and due to the state’s new revenue source from online sales. This is in addition to the projected $1 billion in extra revenues predicted for the 2020-2021 fiscal year.

New job. A hearty welcome to Ashley Henyan, new executive director of the Lowcountry Chapter of the American Red Cross. She comes from the Red Cross of Georgia where she served on the communications team, primarily focusing on media relations.

- Have a comment? Send to: editor@charlestoncurrents.com

Got something to say? Let us know by mail or email

We’d love to get your impact in one or more ways:

Send us a letter: We love hearing from readers. Comments are limited to 250 words or less. Please include your name and contact information. Send your letters to: editor@charlestoncurrents.com. | Read our feedback policy.

Tell us what you love about the Lowcountry. Send a short comment – 100 words to 150 words – that describes something you really enjoy about the Lowcountry. It can be big or small. It can be a place, a thing or something you see. It might the bakery where you get a morning croissant or a business or government entity doing a good job. We’ll highlight your entry in a coming issue of Charleston Currents. We look forward to hearing from you.

Pointy top

Here’s a building somewhere in the Lowcountry for you to identify. Send your guess to: editor@charlestoncurrents.com. And don’t forget to include your name and the town in which you live.

Our previous Mystery Photo

We had lots of great guesses for our Jan. 6 mystery, “Tunnel of trees. Guesses ranged from somewhere on Hilton Head Island or Edisto Island to River Road in Charleston County. But the tunnel was on Mary Murray Drive at Hampton Park adjacent to The Citadel. The camera can be deceiving!

We had lots of great guesses for our Jan. 6 mystery, “Tunnel of trees. Guesses ranged from somewhere on Hilton Head Island or Edisto Island to River Road in Charleston County. But the tunnel was on Mary Murray Drive at Hampton Park adjacent to The Citadel. The camera can be deceiving!

Congratulations to this week’s eagle-eyed sleuths: Chris Brooks of Mount Pleasant; Montez Martin, Stephen Yetman and Kristina Wheeler, all of Charleston; George Graf of Palmyra, Va.; and Archie Burkel of James Island.

Graf said the mystery was difficult and that he spent a lot of time searching on Edisto Island. He finally figured out it was the tunnel of trees adjacent to The Citadel along Hampton Park on what once was a horse racetrack.

- Send us a mystery: If you have a photo that you believe will stump readers, send it along (but make sure to tell us what it is because it may stump us too!) Send it along to editor@charlestoncurrents.com.

A history of our General Assembly

Editor’s Note: With the annual legislative session starting Tuesday, we thought you’d find this (long and sometimes sordid) history of the S.C. General Assembly to be interesting and helpful.

S.C. Encyclopedia | Much of the evolution of the South Carolina General Assembly revolves around attempts by conflicting factions to preserve or gain an advantage in representation. For example, increasingly powerful Carolina-based leaders struggled with proprietary and royal authorities during the colonial era to establish the dominance of the Commons House of Assembly as a basis for political independence (1670–1776). For much of the following century, the burgeoning upcountry struggled against an entrenched lowcountry elite to increase its representation and influence in the legislature. In the social, economic, and political fallout during the decades after the Civil War, racial conflict dominated as a white minority struggled to maintain control of the General Assembly against the challenges of Reconstruction and the civil rights movement. After 1965, federally mandated redistricting and the creation of single member districts weakened rural delegations in favor of the state’s expanding urban and suburban population.

In the earliest years of South Carolina, the Lords Proprietors exercised lawmaking and taxing powers granted them by the king of England to establish a New World colony. The proprietors lived in England, so they selected a governor and, along with major resident landowners, a Grand Council to conduct the affairs of the colony. The proprietors retained veto authority over any Grand Council action. The Grand Council consisted of three groups: representatives of the proprietors, ten colonists chosen by leading landowners to act as a kind of upper legislative house, and a lower or Commons House of Assembly, which consisted of twenty members chosen by the “freemen” of the colony. The Commons House could only discuss proposals from other parts of the Grand Council. After 1682, however, all three groups had to approve any act, thus letting the Commons House exercise legislative initiative. This arrangement stayed intact until the proprietors were overthrown early in the eighteenth century by the general dissatisfaction of the Commons House, which was irked that their legislative initiatives were consistently vetoed by the proprietors.

Reestablished as a royal colony in 1719, a new legislative body was created consisting of two houses. An upper house was designated His Majesty’s Council (or Royal Council) and was composed of twelve persons appointed by the king to unlimited terms. The Commons House continued as a lower house, but this time with members elected by the colonists. To qualify as a Commons House member, one had to own five hundred acres and ten slaves or houses and town lots worth £1,000. Only adult white males could serve, and they did not have to be a resident of the parish from which they were elected. To be able to vote for a representative, one had to be a free white male, at least twenty-one years old who professed the Christian religion, a resident for one year, and own a freehold of fifty acres or pay twenty shillings a year in taxes to the colony. The governor was now sent over from England for the term of his service.

The Commons House continued to gain political momentum during the colonial era, especially by insisting on the right to draft bills about money. The colony gradually became an independent place, made rich by self-made men who used the Commons House to promote their interests while protecting themselves against unwanted challenges from the enslaved population or Native Americans.

From 1769 until the start of the Revolutionary War, the Commons House virtually ceased to function as a result of its involvement in the “Wilkes Fund Controversy.” John Wilkes attacked King George III in his newspaper and was charged with criminal libel. Wilkes became a symbol of the importance of a free press, of protection from unlawful arrest, and of the right of the people to elect any person “not disqualified” to Parliament. South Carolinians supported Wilkes, and the Commons House in 1769 authorized money to help him pay his debts—an act that was an affront to the king. In the aftermath, the Commons House deadlocked with the Royal Council, and civil government came to a virtual standstill.

The first state constitution in 1776 established a two-house legislative branch. The lower house, with 202 members, was elected by eligible voters from election districts made up of the parishes of the now disestablished Anglican Church. The lower house elected a thirteen member upper house called the Legislative Council. Both houses elected a president, who served as governor with a veto power, but who could not be reelected. In 1778 a new constitution renamed the president as governor, called the upper house, the Senate, and allocated additional lower house seats to the upcountry. Despite having a larger share of the state’s free population, the upcountry only received about forty percent of lower house seats. The political center of government remained in Charleston.

In 1788 a state convention met in Charleston to consider ratification of the new U.S. Constitution. The delegates were selected in the same lowcountry-dominated proportions as seats in the General Assembly. The new constitution was ratified by the convention, with most lowcountry delegates supporting it and most upcountry delegates opposing. Upcountry interests immediately pressed for a new convention to deal with representation issues in the state. In the resulting 1790 constitution, counties became the basis for upcountry representation, while parishes remained the representation basis for the lowcountry. Both houses were elected by the people. The lower house was reduced to 124 members, a number which has continued to the present. The vote was still restricted to white males over twenty-one who owned fifty acres or a town lot. House members had to own five hundred acres and ten slaves; senators had to have twice these amounts. The General Assembly not only made laws, but elected the governor, judges, and many local officials.

In the so-called Compromise of 1808, the representation arrangements were changed so that election districts would have one representative for 1/62 of the state’s population and one representative for 1/62 of its taxable wealth. Each election district would have one senator, except for the city of Charleston which would have two. By recognizing population, the upcountry gained a sixteen vote majority in the lower house and a one vote majority in the Senate. This legislative system continued until the Civil War.

Federally appointed officials temporarily took control of the state after the Civil War. A fresh constitution was devised by whites in 1865, which differed but slightly from the 1790 version. Wealth and population continued as the basis for Senate and House members. Although qualified voters were allowed to elect the governor and presidential electors, the newly emancipated black population was barred from voting. The new General Assembly ratified the Thirteenth Amendment that ended slavery, but refused to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, which gave civil rights to blacks. In addition the assembly enacted Black Codes that severely limited the rights and privileges of African Americans in the state. In response Congress closed down the state government in 1867 and demanded a new constitution that would recognize the citizenship rights of black South Carolinians.

Federally appointed officials temporarily took control of the state after the Civil War. A fresh constitution was devised by whites in 1865, which differed but slightly from the 1790 version. Wealth and population continued as the basis for Senate and House members. Although qualified voters were allowed to elect the governor and presidential electors, the newly emancipated black population was barred from voting. The new General Assembly ratified the Thirteenth Amendment that ended slavery, but refused to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, which gave civil rights to blacks. In addition the assembly enacted Black Codes that severely limited the rights and privileges of African Americans in the state. In response Congress closed down the state government in 1867 and demanded a new constitution that would recognize the citizenship rights of black South Carolinians.

The constitutional convention in 1868 was composed of seventy-six black and thirty-eight white delegates. Population alone became the basis for representation and the vote was provided for all males, regardless of race. The General Assembly struggled with issues such as funding a system of public education, rebuilding infrastructure, revitalizing the economy, and countering white opposition to Reconstruction. Spurred by the retreat of federal authority in the mid-1870s, white Democrats regained control of the General Assembly in 1876 and a one-party political system gradually emerged as a way to reestablish and ensure white supremacy.

By 1890 South Carolina looked a lot like it would look in 1950. Agriculture had turned into an established sharecropping system dependent on cotton; the building of railroads had created a new “small town” elite; textile mills had begun to migrate south; and Republicans—the hated party of Lincoln—had virtually disap- peared from the state’s political landscape. Under these conditions, political conservatives—the elites and former Confederate leaders— came to prominence, but did little to relieve the discontent of white farmers who fumed over low prices, high interest and freight rates, and suspicion that the Conservatives were using black voters to stifle legislative responses to their needs.

One leader, Benjamin R. Tillman, was able to articulate the farmers’ problems and set events in motion that produced yet another constitutional convention in 1895. The apparatus of government was not changed very much, but the politics were. One purpose was to get around the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which gave blacks the right to vote. To counter this, white delegates inserted a clause in the new state constitution that limited the right to vote to adult males who had paid a poll tax six months before the election and who were not guilty of certain crimes. The assumption was that most poor persons, especially blacks, could not pay the tax that early and, even if they did, would not subsequently be able to save a receipt to prove it. Even after passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920 extended the vote to women, the electorate in South Carolina remained restricted to “acceptable” whites and blacks.

The continuation of counties as election districts gave rise to a “one county-one senator” system of representation in the General Assembly. The county, not population, was the basis for legislative representation. Each county was also apportioned at least one House member. In 1895 there were thirty-five counties. The number grew to forty-six by 1919. State senators dominated the politics and programs of their county through passage of annual “supply bills,” by which they controlled their county’s budget and most aspects of local government. Since no senator could oppose another’s supply bill without risking opposition to his own, legislative approval for a county’s schools, roads, courts, law enforcement, or other county purposes really rested in the hands of the senator. House members were dependent on what the senator wanted.

As “emperors of a county-based empire,” state senators were extraordinarily powerful political figures well into the twentieth century and the linchpins of the one-party system. Senator Edgar Brown of Barnwell County is perhaps the most potent example of a dominant senator. Speaker of the House Solomon Blatt, also of Barnwell County, advanced rural power in the S.C. House by appointing only one member from each county to a committee, thereby assuring that small counties would outnumber urban counties in most instances. Blatt and Brown were referred to by their critics as the “Barnwell Ring,” but more realistically the reference was to a statewide, rural “ring” that excluded growing urban areas from meaningful political power.

The power of rural delegations faced significant changes as national civil rights policies emerged. First the national Voting Rights Act of 1965 extended full voting rights to every individual regardless of race. An expanded electorate gradually demonstrated political success in gaining minority representation in the General Assembly. John Felder, Herbert Fielding, and I. S. Leevy Johnson, elected to the S.C. House in 1970, and I. DeQuincey Newman, elected to the S.C. Senate in 1983, became the first African Americans elected to the General Assembly in the twentieth century.

Next the county delegation system was fundamentally altered by U.S. Supreme Court decisions that mandated population as the basis for representation and prohibited gerrymandering, the arrangement of political district boundaries for the advantage of a particular interest. New districts with equal population per legislator would now have to be drawn after each national census. In 1971 the House first reapportioned in a plan that retained one representative per county. The tactic did not pass federal courts and the House subsequently reapportioned into single member districts on the “one person, one vote” principle. The Senate in 1968 tried a plan of twenty multimember districts through which each senator represented approximately the same number of people. After the 1970 census, forty-six senators were elected from sixteen districts. After 1980, however, the Senate moved to single member districts.

Election districts are adjusted every ten years to reflect changes in population. The redistricting decisions are in the hands of incumbent state legislators, although their decisions are subject to approval by the U.S. Department of Justice and have typically been challenged in federal courts. Since 2001, Republicans have had a majority in both houses and have allocated important committee assignments by party affiliation rather than by years of service. Legislative party caucuses have become more influential in raising campaign money. In addition to the Republicans and Democrats, African American legislators are organized into a separate caucus. The low number of women elected to the General Assembly continues as a topic of political comment by legislative observers. In 2003 only sixteen members of the General Assembly were women, the smallest percentage of female state legislators in the nation.

Contemporary legislators are aided in their work by increased staff support, computer assisted bill management, and the use of individual offices. Annual sessions begin in January and continue until May or June. Many study committees continue throughout the interim. A new General Assembly is convened every two years after November elections in even numbered years. House members are elected for two-year terms and senators are elected for four years. Each must reside in the district from which elected. House members must be a qualified elector at least twenty-one years of age and senators must be twenty-five years old.

– Excerpted from the entry by Cole Blease Graham Jr. This entry may not have been updated since 2006. To read more about this or 2,000 other entries about South Carolina, check out The South Carolina Encyclopedia by USC Press. (Information used by permission.)

Charleston Comedy Festival offers 26 shows Jan. 15-18

Staff reports | You can get ya after ya out Jan. 15 to Jan. 18 at any of 26 shows offered during the 17th annual Charleston Comedy Festival, the Southeast’s premier comedy event.

The Charleston City Paper and Theatre 99 have teamed up to bring laughter and comedic relief to cure the post-holiday blues.

This year’s event promises to be an even bigger hit than years before with big-name acts—plus more performances, venues, and attendees. Headliners on Jan. 17 include Beth Stelling (7:30 p.m.) followed Francis Ellis (9:30 p.m.), both at the Woolfe Street Playhouse, 34 Woolfe Street. Pete Dominick will perform at 7:30 p.m., Jan. 18, at the same location.

Performers and comedy troupes from the country’s top comedy hotbeds have been invited to perform during the four-day event featuring stand-up, sketch, and improv performers.

- Click here for a list of all shows and prices. Don’t let Daddy take the T-Bird away. Have fun at the festival.

Also on the calendar:

![]() Inauguration day in Charleston: Noon, Jan. 13, Charleston City Hall, 80 Broad St., Charleston. Charleston Mayor John Tecklenburg and six members of city council will be sworn in with a free reception following in Washington Square. Then at 6 p.m., the Cannon Street Arts Center, 134 Cannon St., will host an inauguration celebration with live music, dancing, drinks and light fare. Tickets are $50 each. For more information, go to CharlestonTogether.org.

Inauguration day in Charleston: Noon, Jan. 13, Charleston City Hall, 80 Broad St., Charleston. Charleston Mayor John Tecklenburg and six members of city council will be sworn in with a free reception following in Washington Square. Then at 6 p.m., the Cannon Street Arts Center, 134 Cannon St., will host an inauguration celebration with live music, dancing, drinks and light fare. Tickets are $50 each. For more information, go to CharlestonTogether.org.

Ahead at Gaillard Center: Enjoy something a little different (perhaps) in January at the Charleston Gaillard Center on Calhoun Street:

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra: 7:30 p.m., Jan. 14. Led by conductor Mark Wigglesworth and featuring pianist Olga Kern, RPO will perform Dove Sunshine, Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No.2, and Sibelius Symphony No.2. Tickets are $25 to $119.

From Russians With Love: 7:30 p.m., Jan. 23. The Charleston Symphony Orchestra will offer an evening of Russian symphonic and popular music, including Flight of the Bumblebee, Firebird, Night on Bald Mountain, and of course, From Russia with Love. Tickets are $25 to $114.

Vintage Market returns: 9 a.m. to 3 p.m., Jan. 19, Park Cafe, Rutledge Avenue, Charleston. The Holy City Vintage Market will offer vintage galore and more with great deals on affordable, unique and sustainable stuff. Park Cafe will serve up the brunch goods, including shirred eggs with cauliflower and kale cream, poached eggs, and a parmesan baguette (yum). Don’t forget to sip (a mimosa or Charleston Fog?) and shop, and repeat. More via Facebook.

Charleston Boat Show: Jan. 24-26, Charleston Area Convention Center, 5001 Coliseum Dr., North Charleston. The 40th anniversary of the show will offer the best in boating to thousands who attend the three-day event. There will be more than 85 boat brands and more than 100 vendors selling marine related products and services. The Charleston Boat Show tickets range from $5-$20. For tickets and details please visit www.TheCharlestonBoatShow.com.

Black America: Resilient: Through Jan. 25, 2020, Redux Contemporary Art Center, 1056 King St., Charleston. The center offers this solo show that highlights the work of Dontré Major, a College of Charleston art graduate whose work takes a look at Black/African Americans in the United States during different periods throughout time. Each photograph is meant to emulate the feelings individuals had during these specific times, and touch on the struggle they went through to be seen as equals.

North Charleston art shows: Open daily through Jan. 31, North Charleston City Gallery, Charleston Area Convention Center, 5001 Coliseum Drive, North Charleston. On display are paintings by Pinopolis artist Katherine Hester in an exhibit titled Ebb and Flow and photographs by North Charleston photographer Jenion Tyson in A Bug’s Eye View: Macro Photograph in the Garden. Admission is free.

Lights of Magnolia: 5:30 p.m. to 9:30 p.m., through March 15, 2020, Magnolia Plantation and Gardens, West Ashley. Enjoy nine acres of Chinese lanterns, dragons and more at the venerable garden’s new evening attraction. The lantern festival includes custom-designed installations of large-scale thematically unified lanterns, a fusion of historic Chinese cultural symbols and images that represent the flora and fauna of Magnolia. Learn more online. Tickets are $11-$26. On-site parking is limited, but shuttles are available. For more information and frequently asked questions, click here.

Early morning bird walks at Caw Caw: 8:30 a.m. every Wednesday and Saturday, Caw Caw Interpretive Center, Ravenel. You can learn about habitats and birds, butterflies and other organisms in this two-hour session. Registration is not required, but participants are to be 15 and up. $10 per person or free to Gold Pass holders. More: http://www.CharlestonCountyParks.com.

- If you have an event to list on our calendar, please send it to feedback@charlestoncurrents.com for consideration. The calendar is updated weekly on Mondays.

If you like what you’ve been reading, how about considering a contribution so that we can continue to provide you with good news about Charleston and the Lowcountry. Interested? Just click the image below.

OUR UNDERWRITERS

Charleston Currents is an underwriter-supported weekly online journal of good news about the Charleston area and Lowcountry of South Carolina.

- Meet our underwriters

- To learn more about how your organization or business can benefit, click here to contact us. Or give us a holler on the phone at: 843.670.3996.

OUR TEAM

Charleston Currents offers insightful community comment and good news on events each week. It cuts through the information clutter to offer the best of what’s happening locally.

- Mailing address: 1316 Rutledge Avenue | Charleston, SC 29403

- Phone: 843.670.3996

Charleston Currents is provided to you weekly by:

- Editor and publisher: Andy Brack, 843.670.3996

- Contributing editor, common good, Fred Palm

- Contributing editor, money: Kyra Morris

- Contributing editor, Palmetto Poem: Marjory Wentworth

- Contributing editor, real estate: Digit Matheny

- Contributing photographer: Rob Byko

SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE

Subscriptions to Charleston Currents are free.

- Click here to subscribe.

- Unsubscribe. We don’t want to lose you as a reader of Charleston Currents, but if you must unsubscribe, you will have to do it through the email edition you receive. Just go to the bottom of any of your weekly newsletters and click the “unsubscribe” function. If that doesn’t work, please send us an email with the word “unsubscribe” in the subject line.

- © 2008-2019, City Paper Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved. Charleston Currents is published every Monday by City Paper Publishing LLC, 1316 Rutledge Ave., Charleston, SC 29403.

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!

Pingback: 1/13: MLK events; Finish job on 4K education; Comedy fest – Charleston Currents – Super Black Goals