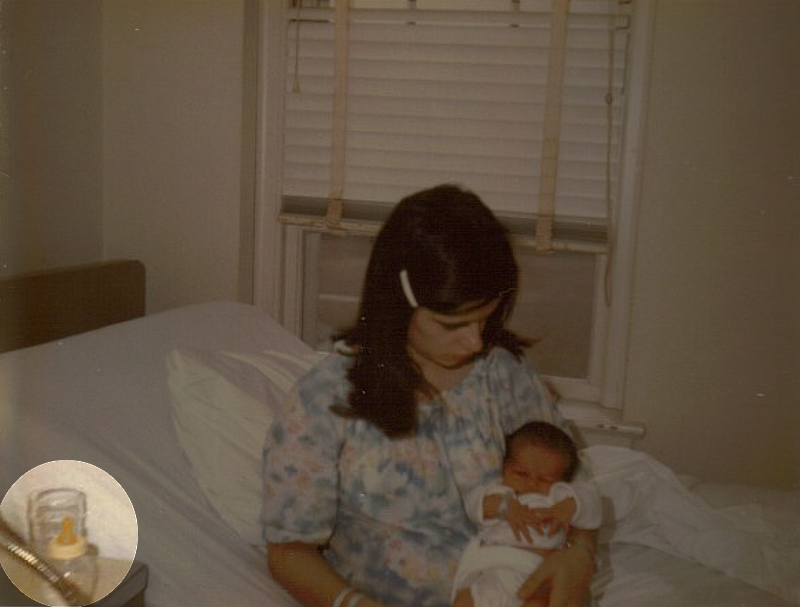

Partain, being held by his mother on the day he was born at Camp Lejeune. Water bottle in bottom left. Provided.

By Andy Brack, editor and publisher | They drank the water. And it’s been killing them.

Retired Navy Chaplain Bruce Hill of Lakeland, Fla., had five years of treatment before his leukemia went into remission. His wife died of breast cancer. His daughter suffers from an inflammatory bowel disease that compromises her body’s immune system. They all drank the water.

Retired Navy Chaplain Bruce Hill of Lakeland, Fla., had five years of treatment before his leukemia went into remission. His wife died of breast cancer. His daughter suffers from an inflammatory bowel disease that compromises her body’s immune system. They all drank the water.

On the day that Mike Partain of Winter Haven, Fla., was born in a base hospital at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina, he, too, drank the water. You can see a baby bottle half-filled with water in the foreground of a picture in my office that shows Mike’s mother holding him hours after he was born.

“If it hadn’t been for a fortunate hug, I’d probably be dead now,” Mike said earlier this year. “I had breast cancer. I’m one of 125 men who had the unique commonality of exposure to the contaminated water at the base and male breast cancer.

“I do not drink. I do not have the BRCA 1 and 2 mutations for breast cancer…. I don’t do drugs. There’s no history of breast cancer in my family. But yet, I get a rare disease but it’s tied to these chemicals.”

From 1953 to 1987, more than 900,000 Marines, their families and civilian employees at Camp Lejeune drank water contaminated by toxic chemicals like gasoline and jet fuel that leaked into wells around the base. Across the country, 273,433 people have registered with the Marine Corps to receive notifications about the poisonous drinking water at Camp Lejeune. More than 7,600 live in South Carolina.

In the 1960s and 1970s at the base, “levels of certain cancer-causing chemicals were among the highest ever recorded in a public drinking water supply,” according to a 2013 Associated Press story.

People like Bruce and Mike got sick. Too many died from diseases like leukemia and cancer — rectal cancer, breast cancer, cervical cancer, ovarian cancer, brain cancer, kidney cancer. Often, it took years for devastating diseases to manifest.

What makes the whole mess even sadder is that the military knew about it for years, but did nothing. All the while, Marines protecting their country had no idea they were battling an invisible enemy — an enemy in the water underneath the homes in which they lived, the offices where they worked, the fields in which they trained.

By 2012, Congress passed a measure to provide limited health care relief for Camp Lejeune veterans, but the law didn’t provide substantial and equitable relief or reimbursement for military dependents and civilian employees who suffered from drinking the polluted water. In other words, some health treatments were covered, but not claims for other damages from victims. Why? Because of a quirk in North Carolina’s law that courts said must be applied before cases could be brought. That limitation has kept those affected by the water from having their day in court.

The only way that’s left to deal with this aberration in North Carolina’s law is for Congress to pass a special bill, the Camp Lejeune Justice Act. If passed, the measure would allow Marines, their families and civilian workers at Camp Lejeune who either consumed or bathed in toxic water for at least 30 days between August 1953 and December 1987 to seek damages and, if denied, to file a lawsuit.

More than 50 members of Congress currently co-sponsor the legislation, but it’s been crawling at a snail’s pace.

Congress, now is the time to get the job done. No more messing around. No more political side steps. Victims and families have suffered for too long. More are dying without relief. Honor the Marines and other sickened victims of this tragic poisoning now by doing the right thing and letting them seek the recovery and peace they deserve.

They protected us. Now let’s do the right thing for them to rectify the toxic wrongs done to them.

Andy Brack is editor and publisher of Charleston Currents, and publisher of the Charleston City Paper. Have a comment? Send to: editor@charlestoncurrents.com.

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!