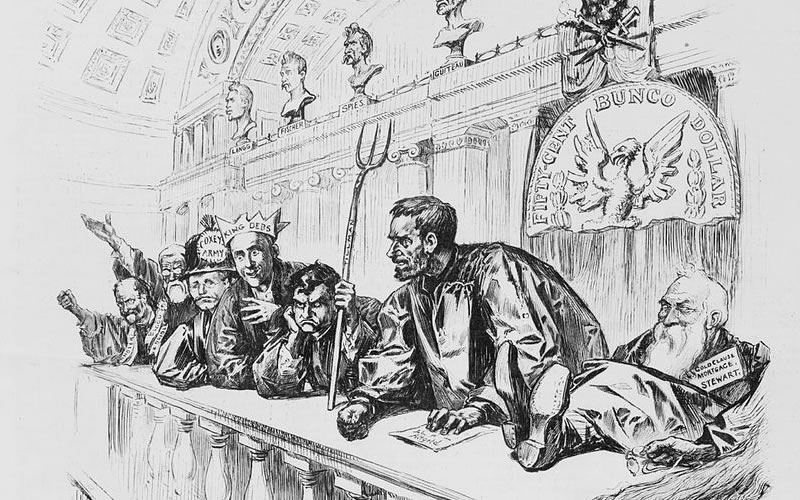

S.C. populist Ben Tillman is holding a pitchfork in this Harper’s Weekly illustration of what a Supreme Court might look like if William Jennings Bryan won the 1896 election. Source: Wikipedia.

S.C. Encyclopedia | Benjamin Ryan Tillman was born in Edgefield District on August 11, 1847, to Benjamin and Sophia Tillman. The family was wealthy in land and slaves, and Ben Tillman was educated in local schoolhouses and on the family’s acres. A serious illness at the age of sixteen cost him his left eye, and his convalescence kept him out of Confederate service. In 1868 he married Sallie Starke. They had seven children.

In the mid-1870s Tillman joined the Sweetwater Sabre Club and became part of the paramilitary rifle-club movement, through which white landowners challenged the Republican state government. He took part in the Hamburg Massacre (July 1876), in which rifle-club members (known thereafter as “Red Shirts”) besieged a black militia unit and murdered several captives. Tillman later explained that “the leading white men of Edgefield” had determined “to seize the first opportunity that the negroes might offer them to provoke a riot and teach the negroes a lesson.” The massacre fractured compromise arrangements between state Democrats and Republicans and helped create the electoral crisis of 1876–1877.

Over the next few years, the failure of Democratic leaders to address the impoverishment of most white households inspired challenges from Martin Gary, who portrayed the Red Shirts as the latest upcountrymen to be treated unfairly by lowcountry leaders, and from the interracial Greenback-Republican alliance, comprised of whites discontented with elite control of the Democratic Party and black Republicans. In 1882 this alliance posed a serious enough challenge that the Democrats responded with paramilitary force. Tillman, an active member of the Red Shirt “Edgefield Hussars,” learned two lessons from these campaigns: that the Democratic Party, having failed to meet the needs of most white men, remained vulnerable to interracial political alliances; and that the tradition of conflict between upcountry and low<\h>country offered Tillman a platform for uniting a majority of white South Carolinians against both conservative Democratic leadership and African Americans voters.

Tillman

During the mid-1880s Tillman presented himself as the champion of “the farmers” against lawyers, politicians, merchants, “aristocrats,” and “Bourbons,” whom he blamed for the hardship common to white agricultural households. Through the meetings of his Farmers’ Association, he called for reform in education, agriculture, taxation, and legislative apportionment. The centerpiece of his agenda became the establishment of a “farmers college,” and in 1886 he and other proponents of practical agricultural education met with Thomas Green Clemson, heir to John C. Calhoun’s estate, and encouraged Clemson to use his will to help further this project.

Though Tillman was the leader of the “Farmers” movement (also known as the “Reform” or “Tillman” movement), he was most effective as a gadfly. In newspapers and on the stump, Tillman denounced the state’s leadership as a “ring” of “broken-down politicians and old superannuated Bourbon aristocrats, who are thoroughly incompetent, who worship the past, and are incapable of progress of any sort, but who boldly assume to govern us by divine right.” Their educational institutions demonstrated their uselessness: South Carolina College produced “helpless beings,” while the Citadel was “a military dude factory.” Further, he charged elected officials with malfeasance and corruption, often insinuating that particular men were to blame but then denying having done so.

Tillman’s efforts soon bore political fruit. In 1888 Clemson’s bequest came before the legislature just as the Farmers Alliance, a protest vehicle for hard-pressed farmers, arrived in South Carolina. Tillman presented himself as the champion of both the college and the alliance, and in 1890, despite significant opposition and a bitter convention fight, he won the Democratic nomination for governor. He then faced a challenge from disgruntled conservative Alexander C. Haskell, who appealed for black electoral support. This betrayal of white supremacy made Haskell unappealing even to those who opposed Tillman’s policies and methods. Tillman was also able to use racial fears to defeat radical alliance members who supported the People’s Party, better known as the Populists. He argued that Populists’ insistence on federal intervention in the economy, coupled with their support for black voting rights, threatened a return to the political, economic, and racial evils of Reconstruction. By 1892, when he ran for reelection, Tillman offered himself to white farmers as a sensible alternative to President Grover Cleveland’s economic conservatism on one side and the Populists’ radicalism on the other.

As governor, Tillman made reforms that were more symbolic than substantive. He oversaw the establishment of Clemson College for white men and Winthrop College for white women, but he remained less committed to the practice of higher education than to the principle of white supremacy. In 1891 he refused federal aid for Clemson if that would require him to accept a proportionate amount of aid for black higher education at Claflin. He took popular but economically inconsequential stands against railroads and the state-chartered phosphate monopoly. He established a state liquor monopoly, the “Dispensary,” which provided him with unprecedented patronage power. Conflicts over the law and its enforcement by state-appointed constables led to a showdown and political crisis in the town of Darlington in 1893, the “Darlington Riot.”

Tillman’s most important contribution to South Carolina’s political life came with the Constitutional Convention of 1895. Tillman argued that only a revision of the laws regarding electoral qualification could safeguard the state from a potential black Republican resurgence. His promise that no white man would lose his vote was greeted with skepticism. The 1894 referendum on whether to call a convention was fiercely contested, as Sampson Pope, formerly a Tillmanite, left the Democratic Party to run an indepen<\h>dent campaign for governor and against the convention referendum. While Pope earned only about thirty percent of the vote, the convention referendum was much closer and proconvention forces won their narrow victory amid accusations of electoral fraud.

Tillman helped draft a constitution under which men had to own substantial taxable property, prove their literacy, or demonstrate “understanding” of the constitution in order to register to vote. The “understanding” clause was adopted in order to allow white Democratic officials to discriminate on racial and partisan grounds. Like most of his colleagues, Tillman also rejected arguments made by some white female suffragists that granting voting rights to women could establish a less obviously fraudulent electoral bulwark for white supremacy. Politics, Tillman believed, ought to remain the province of white men.

In 1895 Tillman entered the U.S. Senate, where he achieved notoriety for his rhetorical attacks on racial equality, corporate power, and imperial expansion. Tillman’s lifelong hostility to black freedom gained particular infamy. Though Tillman frequently condemned lynching as an assault on the authority of the state, he made one great exception in 1892, when he publicly pledged that in cases in which a black man was accused of raping a white woman, he would lead the lynch mob. Tillman never actually put his pledge into practice, but he did on occasion collude with lynch mobs. In one 1893 case, Tillman sent a black rape suspect, protected by only a single guard, to face a crowd of many hundreds. The man was lynched. Tillman argued that white male violence toward accused black rapists was a product of their instinct for “race preservation,” a force so powerful that it could cause “the very highest and best men we have [to] lose all semblance of Christian human beings.”

Tillman made his “race problem” speech before hundreds of audiences nationwide. He also spoke against “trusts and monopolies” and U.S. imperialism. In his maiden Senate speech, “Bimetallism or Industrial Slavery,” and countless sequels, he suggested that the “money power” was hard at work against the interests of farmers and workers. In his view, Republicans conspired with corporations to raise prices on imported goods, lower the wages of industrial workers, and subordinate the southern economy. Imperial expansion would benefit corporations while undermining democracy, either through the corruptions of empire or by incorporating millions of nonwhites into a nation where white supremacy had been under siege since 1865.

Nationally most journalists and public officials initially perceived Tillman as a “wild man.” This impression drew credibility from many sources: Tillman’s frequent boast that in 1876 “we shot negroes and stuffed ballot boxes”; his threat to stick a pitchfork into Grover Cleveland; his part in the successful defense of his nephew James Tillman, who murdered the journalist Narciso Gonzales; and his 1902 fistfight on the Senate floor with fellow South Carolina senator John McLaurin. But in 1906 Tillman’s reputation began to soften. In an attempt to derail a railroad rate bill, congressional Republicans put it in Tillman’s hands and assumed that the erratic senator would be unable to accomplish anything. However, despite the final bill’s shortcomings, Tillman emerged from the fight with a reputation as an effective reformer. During his last decade, the formerly ardent foe of federal power and champion of “the farmers” helped steer millions of federal military dollars to South Carolina. He also denounced the language and character of his former ally Coleman L. Blease, whose popularity caused Tillman—later lauded as “the friend and leader of the common people”—to question the capacity of men, even white men, for self-government.

In 1908 Tillman endured the first of several debilitating strokes. Shortly before his seventy-first birthday, he suffered a cerebral hemorrhage. Tillman died in Washington, D.C., on July 3, 1918, and was buried in Ebenezer Cemetery in Trenton, South Carolina.

— Excerpted from an entry by Stephen Kantrowitz. This entry hasn’t been updated since 2006. To read more about this or 2,000 other entries about South Carolina, check out The South Carolina Encyclopedia, published in 2006 by USC Press. (Information used by permission.)

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!