S.C. Encyclopedia | James Francis Byrnes was born in Charleston on May 2, 1882, the son of James Francis Byrnes, an Irish Catholic city clerk, and his Irish Catholic wife, Elizabeth McSweeney. Seven weeks before his birth, Byrnes’s father died of tuberculosis, leaving “Jimmy” to be reared by his widowed mother. She had gone briefly to New York to learn dressmaking in order to support him, his sister, an invalid grandmother, an aunt, and a nephew. In his early teens Byrnes left school to work in a Charleston law office to help support the family.

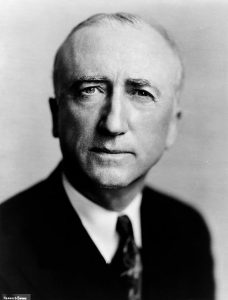

Byrnes

His public career began in 1900 when Judge James Aldrich of Aiken appointed him court stenographer for the six-county Second Judicial Circuit. When not traveling to circuit court sessions between Aiken and Beaufort, Byrnes studied law in Judge Aldrich’s office, and by 1904 he was licensed to practice law. He began singing “barber shop tenor” in the choir of Aiken’s St. Thaddeus Episcopal Church, where Maude Busch, a Converse College student, also sang and attended church. With the blessings of his mother and against the advice of his local parish priest, he married “Miss Maude” on May 2, 1906, and soon after converted to the Episcopal faith. Much to their regret, the marriage was childless.

Over his lifetime Byrnes held many public positions, coming closer than any other South Carolinian in the twentieth century to obtaining the national political influence wielded by John C. Calhoun in the nineteenth century. In 1908 Byrnes was elected circuit court solicitor. At that time solicitors spent part of the year in Columbia assisting legislators in bill drafting. Building on political connections from the circuit court and the legislature, he was elected U.S. congressman and served for fourteen years (1911–1925). He was elected the first time by fifty-seven votes in a primary runoff after campaigning as “a live wire” and “a self-made man.”

During his time in the U.S. House, he formed close relationships with Democratic leader Champ Clark from Missouri and Illinois Republican “Uncle” Joe Cannon. From them he learned how to manage legislation. Byrnes helped establish the first national highway system, including U.S. Highway 1 through his hometown of Aiken, based on payments to states for roads used by mail carriers or in interstate commerce. For Byrnes, federal aid to the states to offset their costs in maintaining national government responsibilities was consistent with the Constitution. Byrnes worked on House appropriations, especially financing military operations during World War I, and came to know Franklin D. Roosevelt. Byrnes was also instrumental in passage of the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921, which consolidated the power of the House Appropriations Committee and created a director of the budget.

In 1924 Byrnes was defeated in a bid for the U.S. Senate by Cole L. Blease. Some Bleasites exploited anti-Catholic feelings in the upstate by circulating a political ad from a Charleston newspaper in which twenty former altar boys at St. Patrick’s Catholic Church had endorsed Byrnes. Byrnes’s adamant refusal to join the revived Ku Klux Klan may have also contributed to his defeat. Afterward, Byrnes took up the practice of law with Sam J. Nicholls and Cecil C. Wyche in Spartanburg. He moved from Aiken because he felt awkward charging fees to his neighbors and political supporters.

Byrnes unseated Blease in 1930 and was elected U.S. senator in 1936. Byrnes had maintained his earlier association with Roosevelt, advising him to run for governor of New York in 1924 and supporting his run for the presidency in 1932. As a senator, Byrnes became an influential advocate of President Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, helping to write many of the emergency economic laws in “the first 100 days” of Roosevelt’s administration. He was instrumental in securing federal funding for the Santee Cooper project. In the 1936 election, Byrnes pointed out that South Carolina had gotten about $24 in federal assistance for each dollar it had paid in federal taxes.

In 1941 Byrnes resigned from the Senate when Roosevelt appointed him associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. While a justice, Byrnes was responsible for fifteen or more decisions. Edwards v. California was his first. Based on the Commerce Clause, this opinion reversed a state court conviction of a man who brought his wife’s unemployed brother into California. At the time, California law forbade knowingly bringing an indigent into the state. In another Byrnes opinion, Ward v. Texas, the Supreme Court reversed a state court murder conviction of an uneducated African American due to an extorted confession. The accused man was subsequently acquitted.

Sixteen months after joining the Supreme Court, in October 1942 Byrnes resigned so that President Roosevelt could appoint him director of the Office of Economic Stabilization, which coordinated federal efforts to control the inflationary effects of increased war spending. In May 1943 Byrnes became director of war mobilization, a position with enough powers to earn him the nickname “Assistant President.” Like Bernard Baruch, who had served President Woodrow Wilson in a similar capacity during World War I, Byrnes was responsible for unifying the nation’s industrial production programs for World War II.

With such a distinguished record, Byrnes was widely rumored to be Roosevelt’s nominee for vice president in 1944. His chances failed after he was opposed by Catholic political leaders who characterized him as a deserter to his native church, by northern minorities who feared him as a segregationist, and by organized labor who opposed his anti-labor-union, right-to-work views. In January 1945 Byrnes accompanied Roosevelt to Yalta for the conference with Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin.

After Roosevelt’s death, Byrnes served as U.S. secretary of state under President Harry Truman from July 3, 1945, until January 20, 1947. His activities were central in defining postwar U.S. foreign policy. Along with President Truman, he was one of four representatives at the Potsdam Conference near Berlin in July 1945, and he confronted ongoing issues among the Allies and the Soviets. A September 1946 speech by Byrnes at Stuttgart, West Germany, countered European fears that the United States would return to isolationism and retreat as a world power. Byrnes reassured the German people that the United States would help reestablish their nation on a sound basis and assist in plans for a provisional government. He also restated the United States’ commitment to maintain troops in Germany. This had the effect of blunting Soviet claims that only they favored German recovery and self-government. The French and the British were also encouraged to accept the Truman administration’s policies for rebuilding postwar Europe, since it was evident that the United States would not sacrifice them for an exclusive American-Soviet friendship.

Byrnes subsequently feuded with Truman over the politics of foreign policy, the appointment of his successor as secretary of state, and a speech at Washington and Lee University in which Byrnes criticized the power of the national government. He returned to Spartanburg but practiced law with a Washington, D.C., firm until spring 1949. Displeased with Truman and the national Democratic Party, Byrnes supported Strom Thurmond’s 1948 “Dixiecrat” bid for president. In the process, he ruptured his old friendship with state senator Edgar A. Brown, whom he had known years before in Aiken.

Nevertheless, Byrnes was elected governor in 1950 in a “welcome home” atmosphere. He proposed some reforms, including more funds for the state hospital for the mentally ill. Central, however, was his position on racial segregation and public education. In his inaugural address in 1951, Byrnes proposed a sales tax to provide “substantial equality” in segregated public school facilities. The legislature subsequently passed a three-percent general sales tax to pay for new school buildings, better school bus transportation, and more organized school districts in an effort to upgrade education for African Americans. As an advocate of the “separate but equal” policy, Byrnes remained a segregationist. Critics saw his stance as a lost opportunity for perhaps the only political leader in the region with sufficient national stature, a “modern day Calhoun,” to exercise the leadership to end racial segregation. Instead, Byrnes blamed “Negro agitators” and “Washington politicians” and even threatened to abandon the public school system rather than desegregate. His politics became more and more distant from the national Democratic Party. In 1952 he endorsed Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Republican presidential candidate, and invited “Ike” to speak from the State House steps in Columbia. Byrnes supported Eisenhower in 1956 and Richard M. Nixon in the 1960 presidential election.

Byrnes wrote two autobiographies, Speaking Frankly (1947) and All in One Lifetime (1958). The royalties were donated to the Byrnes Foundation, which granted college scholarships to South Carolina orphans. Byrnes left a series of political legacies in South Carolina, the nation, and the world. His advocacy of highway and New Deal legislation provided numerous material benefits to South Carolinians. His services to President Roosevelt had a major impact on the national economy during World War II. His role as secretary of state was instrumental in defining postwar foreign policy. In the 1950s and 1960s Byrnes’s support of Republican presidential candidates was a key factor in the party’s revitalization in the South.

After several years of declining health, Byrnes died in his Columbia home on April 9, 1972. He was buried in the Trinity Episcopal Church cemetery.

— Excerpted from an entry by Cole Blease Graham, Jr.. This entry hasn’t been updated since 2006. To read more about this or 2,000 other entries about South Carolina, check out The South Carolina Encyclopedia, published in 2006 by USC Press. (Information used by permission.)

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!