By Andy Brack, editor and publisher | While many visitors to South Carolina focus on its part in the Civil War, they might be surprised to realize that without the Palmetto State’s leading role in American independence, our nation might not have been formed at all.

Not only was South Carolina home to the first major patriot victory on June 28, 1776 at the Battle of Sullivan’s Island, but South Carolina had more battles and skirmishes during the Revolutionary War — some 254 engagements — than any other state. From a tactical standpoint, all of those conflicts had a draining impact on the patriots’ foes, the British. They were forced to battle on two fronts — the South and the North — which extended supply lines and sapped strength.

“Between 1776 and 1778, the British sought to crush the revolution at its heart, which was in the northern colonies,” Francis Marion University history professor Scott Kaufman explained. “When that failed, the British turned to the South. There were more loyalists in the South, and the British hoped that they could gradually gain supporters as they marched through the southern colonies northward, and eventually crush the revolution that way.”

“Between 1776 and 1778, the British sought to crush the revolution at its heart, which was in the northern colonies,” Francis Marion University history professor Scott Kaufman explained. “When that failed, the British turned to the South. There were more loyalists in the South, and the British hoped that they could gradually gain supporters as they marched through the southern colonies northward, and eventually crush the revolution that way.”

At first, it seemed to work. Savannah fell in 1779. The following March, the British lay siege to Charleston, which fell with an army of 5,500 troops in May.

But the British unleashed a bloody campaign of plunder and retribution. Colonial leaders like Francis Marion in the northeast of the state, Andrew Pickens in the Savannah River valley and Thomas Sumter in the Midlands soon incubated modern guerilla warfare — hence all of those battles and skirmishes.

“The so-called ‘partisan war’ that raged in the backcountry — really a brutal, savage guerilla war — between South Carolinians on different sides has some current significance,” noted historian Lacy Ford, who is dean of graduate studies at the University of South Carolina. “South Carolina was once home to clannish, near tribal infighting, with leading backcountry families choosing sides, much like in Afghanistan and Iraq of the past 20 years.”

Kaufman pointed to Marion’s role in particular: “He made it harder for the British to engage in their ‘southern strategy’ during the Revolution. He also made it more difficult for the British to reinforce their positions elsewhere.”

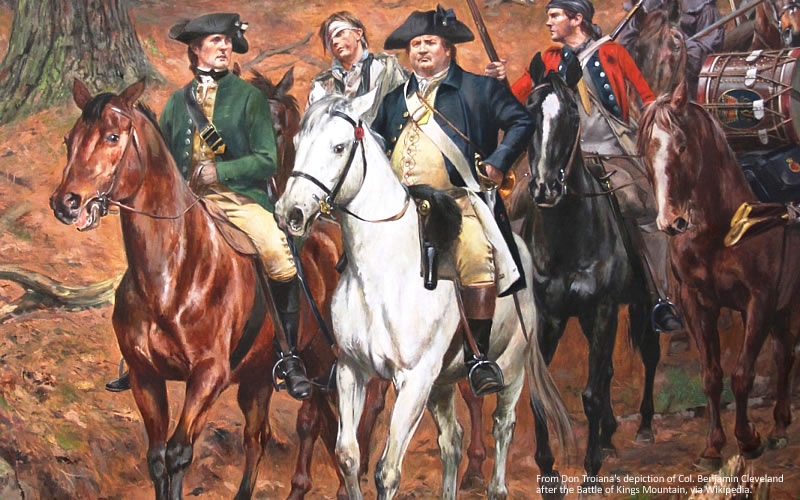

If all of this wasn’t enough, then came the Battle of Kings Mountain in October 1780, which “historians of the period now recognize … as one of the turning points of the Revolution,” noted Jack Bass and Scott Poole in their history of the state. Patriot backwoodsmen threatened by the British routed a loyalist force of 1,100 in Cherokee County. That, in turn, diverted a large British force that was heading north to take on George Washington’s Continental Army.

Three months later at the Battle of Cowpens, also in Cherokee County, the tide of the war turned as the British lost nearly 1,000 men and supplies. As Bass and Poole wrote, the loss forced the British commander, Lord Cornwallis, to “pursue the patriot forces into the interior, a move that began the course of events that led 20 months later to the ruin of Cornwallis at Yorktown” and the end of the war.

Throughout 1781, aided by a new Continental army in the state led by Nathanael Greene, the fighting continued at Hobkirk’s Hill, Ninety Six and Eutaw Springs. By September 1782, British ships landed in still-occupied Charleston and started pulling out troops and 4,200 loyalists who wanted to leave the state. By December, occupiers finished withdrawing and “after 30 months of bloody fighting and brutal occupation, South Carolinians were once again in control of their own affairs … The war may have begun and ended in Charleston, but it was won in the forests and swamps of the back country,” historian Walter Edgar wrote in The South Carolina Encyclopedia.

So as you celebrate July 4 and see the state’s navy flag, realize its white palmetto tree is more than a pretty icon. It’s a symbol of the spongy palmetto logs at a fort on Sullivan’s Island that helped to repulse British cannons just days before the drafting of the Declaration of Independence in what was the first of many South Carolina victories in the American Revolution.

Have a comment? Send to: editor@charlestoncurrents.com

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!